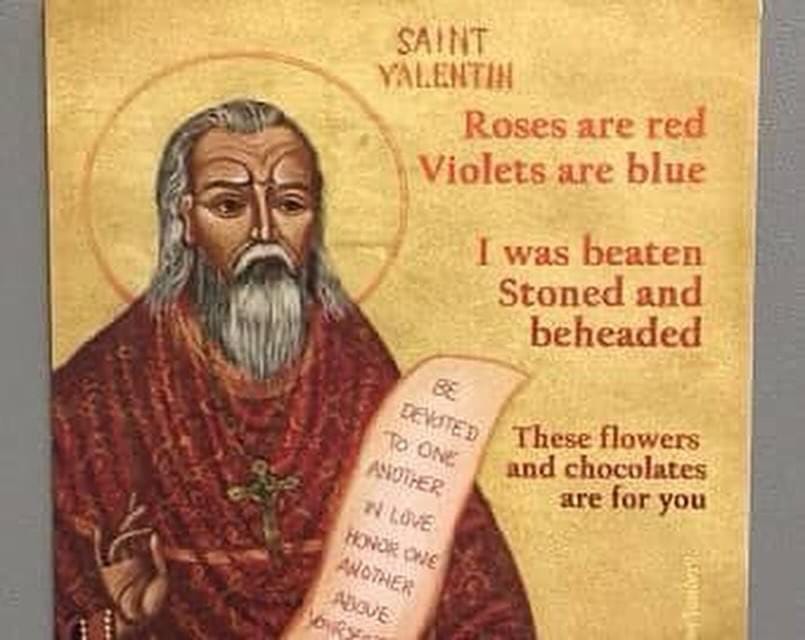

Happy Valentine’s Day and blessed Ash Wednesday. This combination doesn’t happen often, but for Christians, today combines two truths that sit uncomfortably but honestly in our cosmology. The first is that love, as personified in Christ and echoed in His followers like St. Valentine, is real. The second is that without Christ, we all face death. Or in the pithy words of this, erm, love note:

Here on this Ash Wednesday, some of us will have our foreheads or hands marked with ash as a reminder of our sin, our mortality, and the beginning of our Lenten commemorations (to read more about Ash Wednesday, look here). The widespread pagan understanding of love hardly seems to dovetail with this. Our culture would much rather remake love in its own image—that is, a self-deifying individualist pursuit that, due to its insistence on the all-important “my” trumping any other thought or act, ultimately ends in loneliness.

But Christians know that real love is embodied in Christ, who as the living Word, sacrificed Himself for our sakes. With this in mind, I couldn’t help thinking about an event that shockingly highlighted the temporal temptation to turn away from God in the name of “love”: the February 19, 1974 walkout—also known as the Seminex controversy—at Concordia Seminary in St. Louis (CSL).

Those outside of some history-loving circles in the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod or some other niche church outlets have probably never heard of this event. Yet at the time, the hundreds of seminary students and forty professors who left, among others, garnered a lot of media attention, including Time magazine (see the March 4, 1974 and the December 30, 1974 issues). To outsiders, what looked like a silly, fundamentalist kerfuffle in a small so-called Protestant church body was actually an iteration of a fight that had been ongoing since Jesus was born, and truly, since the serpent asked Adam and Eve, “Did God really say…?” Who is the one true God? How has He revealed Himself? Can we trust that the Bible is the inspired word of God and that it is true and unerring? How do we join with other Christians in confessing who God is and what He has done for us?

I learned much more about the walkout and lots of Lutheran history at the recent Tell the Good News about Jesus convocation for laypeople and clergy here in the Wyoming District of the LCMS. You can read a fine theological history of what led up to that February day in 1974 in Kurt Marquart’s Anatomy of an Explosion: Missouri in Lutheran Perspective. It’s a sad but thorough account of what led to a sizeable number of clergy, notably seminary professors, in the LCMS ultimately rejecting biblical inspiration and inerrancy, among other things.

If the Bible is true, then it’s true. If it’s not, there’s no stopping what we can change, toss, or deny in or from it. We can read it carefully, and we should (see the historical grammatical method and this paper on it from 1974, if you want a thorough description). But careful reading doesn’t mean the Bible is like any other human document. It isn’t. Beyond those moved by social pressure, emotional ties, and other real but subjective motives, the primary tie of of those participating in the walkout was a view of the Scriptures that placed it on par with an other text, with predictable results.

As Marquart pointed out, the rationalistic basis for their rejection manifested in the most genuine skeptics in an age-old way: “the external authority of divine revelation seemed embarrassing, if not insulting to his new [rational] dignity.” Suffice it to say, after many deep and well-documented conversations and confessions over centuries, not least the Lutheran Confessions, the walkout became yet another example in church history of people, at best, desiring less onerous doctrinal unity with others for the sake of temporal togetherness. At worst, it reads like a theological version of a teenage tantrum: you can’t tell me what to do; you’re mean; I’m leaving; but it’s your fault I’m leaving.

Of course, that image oversimplifies a lot of the discussion at the time of the walkout as well as how our church discusses it today. Chalk my image up to me being a sinner with my own history of tantrums, a mom of eight sinful children, and a believer who’s also been surrounded with the remnants of the walkout’s consequences for my entire life.1 Read enough church history, of Lutheranism or just about any other church body, and you’ll see the same story played out. When love means speaking God’s truth even when people you care about disagree, someone—and usually multiple people—get hurt. You can see this in some heartbreaking accounts from the time of the walkout in Concordia Historical Institute Quarterly’s latest issue (you can read about the issue here; follow links to become a CHI member). No one was happy about this. And I don’t doubt the sincerity of people on both sides of the walkout. Yet sincerity is not the measure of truth, just as feelings aren’t. We need something, actually Someone, much greater and more lasting than ourselves upon which to ground our hope.

No doubt, love is real. It’s also bitingly piercing, like a diamond, in its truth. It’s both dazzling and cutting. But it remains—because Christ is Love, and He is ours. He has said so, and we still cling to Him and to His words.

Love does not rejoice at wrongdoing, but rejoices with the truth.

1 Corinthians 13:6

From relatives who left Missouri to join other Lutheran churches and eventually church bodies, to the constant higher critical immersion I experienced at Valparaiso University. I could write a book on this.

This, from C.S. Lewis, captures the mistake of those who participated in the walkout for reasons of so-called theological modernization and progress:

“We all want progress. But progress means getting nearer to the place where you want to be. And if you have taken a wrong turning then to go forward does not get you any nearer. If you are on the wrong road progress means doing an about-turn and walking back to the right road and in that case the man who turns back soonest is the most progressive man. There is nothing progressive about being pig-headed and refusing to admit a mistake. And I think if you look at the present state of the world it's pretty plain that humanity has been making some big mistake. We're on the wrong road. And if that is so we must go back. Going back is the quickest way on.”