It’s spring-cleaning time at our house. So Jon is repainting areas, I’m trying to finish clearing and cleaning out closets, and we’re prioritizing projects that require elbow grease and warmer weather (garage, I’m looking at you). It’s an annual ritual, chaotic and fulfilling and at times, counter-productive (I dust and then we open windows. Hello, Wyoming wind!). This time also reminds me of some of my favorite images in Peter Spier’s lovely children’s book, Noah’s Ark.

They aren’t of the tedious construction of the Ark, with the piles of building materials, the enormous project itself rising from the thoroughly dry earth, and the incredulous and scoffing onlookers. (I must say, though, that I do think Spier’s depiction captured the atmosphere of Noah’s faithful dedication among a world that viewed his work as, at absolute best, a harebrained waste of time.) They aren’t of the scenes of the beginning rainfall, the water rising as people and animals outside the Ark at first look on, and then seek to be saved, though I appreciate the nod to the destruction wrought by the flood (this narrative is decidedly not just a sweet story about animals frolicking on a big boat). They’re not the pictures when Noah is pensively walking the deck, waiting to see if the dove returns from the earth where the waters are subsiding, as poignant as his waiting is.

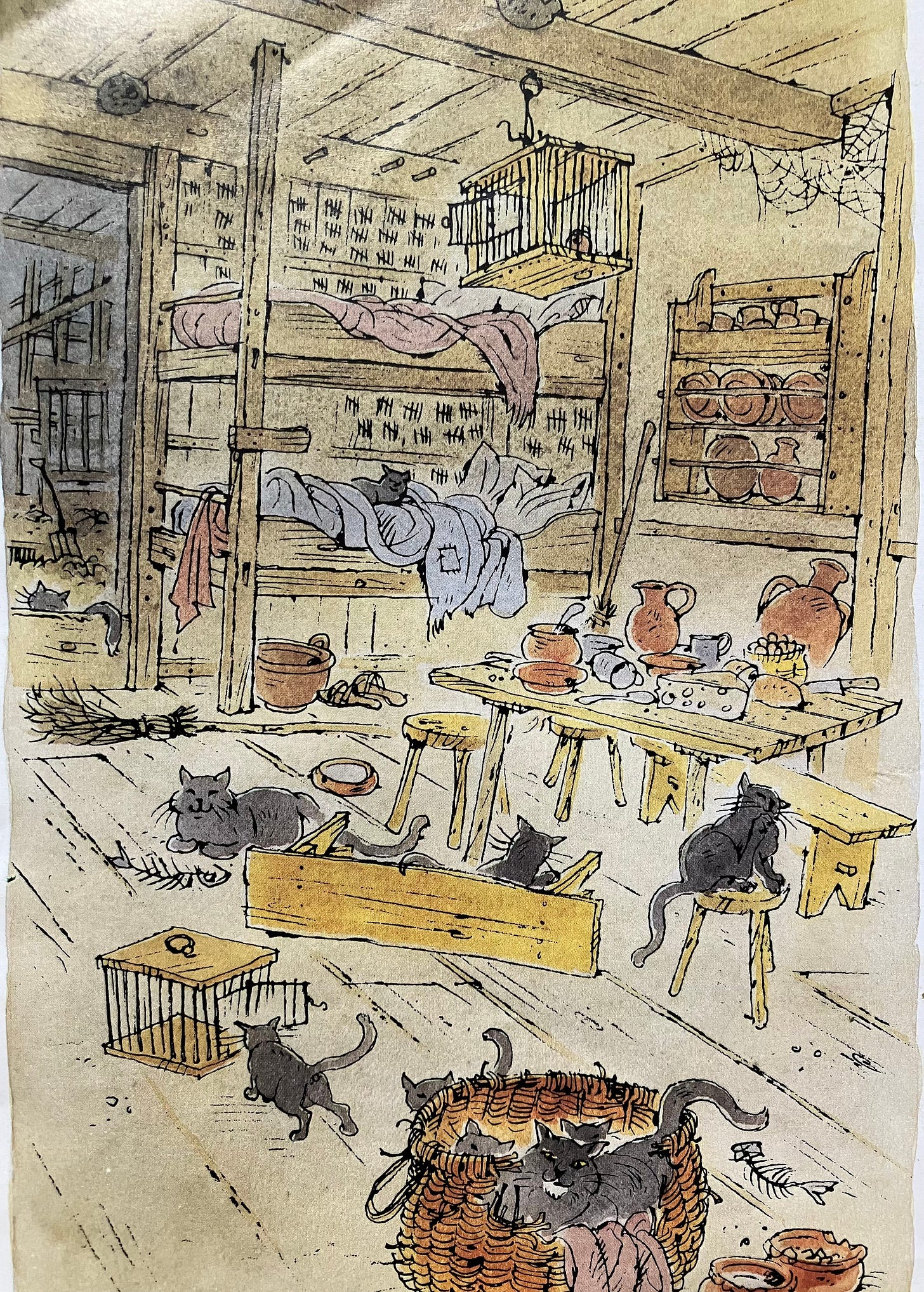

No, my favorite scene appears after the Flood is over and the waters have receded, and the Ark is finally empty. We see the detritus and filth, the cascading leftovers of the family and the zoo that have survived in this craft, floating and isolated for months and months. And the mess is understandably incredible.

I appreciate this moment as a person who very much appreciates cleanliness and neatness, and who doesn’t experience it much—at least, as much as I’d like. I marvel over the picture above partly out of voyeuristic wonder. I was the kid who organized my Christmas gifts neatly in a corner while my siblings tore apart paper and festooned the room with wrapping. Now I am the mom who tries to keep order without becoming too attached to an unattainable vision of pristine life, like HGTV magazine spreads. Or honestly, without losing my mind at the lack of control I hold over the mess.

Once, when we had three or four kids, I made the mistake one day of keeping track of how long it took me to clean the kitchen and dining room floors. We had an infant, and I was still nursing fairly frequently, plus multiple kids underfoot with books and PlayDoh and blocks and crayons and snacks and the like. I had to clear the floor of furniture, then sweep, then mop. Amidst having to sit for at least some of the baby’s feeding times, helping the bigger kids with projects and stories and meals, with requisite get out things and pick up items times, I found myself thoroughly defeated when I finally finished the job. It took me eight hours. Eight. Hours!

Most American mothers, I think, would hear that and think, well of course it took that long. Or that it was pointless for me to even try. Unless I completely ignored my children to single-mindedly focus on the floor, such a drawn-out job was inevitable. But what that experience did was make me depressed about the kind of work I needed to do every day. And the kind of work motherhood can take, especially of the daily humdrum variety, can leave us feeling disheartened. It is not like, say, writing a Substack essay. (Is it?)

This is where I needed a vision of beyond. Not a variation of “the kids are young, embrace the mess” philosophy, though. This holds a grain of truth, that thirty years from now I won’t remember how messy my floor was on a given day. But it doesn’t satisfy the human need for cleanliness and order. And it is a need, just as we need nourishing food and durable shelter and warm, protective clothing. Even Noah, his family, and the animals received the gift of order. But the “embrace the mess” philosophy has not only failed to acknowledge this need; it has also ignored how intimate community has sustained this need for much of human history. I appreciate the Amish tradition of sending single aunts or young unmarried women to help postpartum mothers, and likewise families care for the elderly in their homes. The alienation of much of American suburban life, including the lonely toil of household necessities, doesn’t have much of that. I feel the lack of comradeship when I have to clean the floor myself and do any number of tasks, even when I call my mom or sisters or friends to keep me company (they’re usually doing something else while we chat, too). We all might cringe at the thought of being stuck on a floating hurly-burly with only a few people for far, far longer than the average pleasure cruise, but we also can’t deny that every one of those people would know how valuable his or her labor was, and that they were all literally in the squall together.

So I know how important cleaning and order are, and the mess on the Ark proves not only how much of a wreck living creatures can make of a space; it also proves that life was there.

This is the vision I need, and it’s one Leah Libresco Sargeant writes of in her Substack “Other Feminisms” recently, “I Am What I'll Never See.” Her piece acknowledges our finitude as well as our places in continuous lines of humanity. And these aren’t tenuous strings, though our culture makes them out to be (pushing rot like making your own family comes to mind). Our lives are inextricably bound up in those of our families. They are literally biologically encoded ties linking generation to generation, and social and cultural ones, too, at their best creative confessions of the Lord, continuations of layer upon layer of prior history, interactions and lessons and repeated stories of what is good, true, and beautiful.

Thus histories are not, contrary to American myth, Horatio Algier bootstrap monologues; they are full of father to son, mother to daughter, uncle to niece, aunt to nephew, patriarch to dawdling toddler, young woman to matriarch, neighbor to neighbor handoffs and sharings, a kind of generative, timeless love. Sergeant references cathedral building, how generations of the same family would participate in the construction of an architectural work of art. Some—actually most—of the workers would never see the finished product. But they labored on anyway, hoping and believing that their work would ultimately build a place that testified to the majesty and grace of God.

Sergeant worked in a lab for years, and she wrote of the tedious labor and frequent failures that work entailed. In reflection, she writes that

It reminds me of parenting, where there is constant, quiet work day by day, most of which won’t be remembered as World Historical. It sounds like cathedral building, where for every rose window spangled in light, there are quiet stones setting off the blaze and supporting it.

We’ve all seen photos of decaying buildings; empty farmhouses with broken windows, sagging porches, missing patches of roofs. An abandoned home is usually sad. It speaks to an emptiness following life, a nod to death. But in the Ark, the mess, and the home that was left, are the visceral evidences of the whole point, but not the point itself. The important point is that God gave Noah and his family, and all the living creatures He preserved, a shelter that carried them. In this temporary home, they have passed through the watery wilderness intact. Yes, it is a thoroughly soiled wreck, literally impaled on a mountain and never to move again, with the reek and filth of life permeating its boards until it is taken apart or rots away. The Ark has made its delivery. Now God has given all of the living creatures another, better home, a place He always intended for them to plant and grow.

I can’t pretend that these thoughts will make me cherish tackling kitchen counters covered with dirty dishes, or love sorting soiled clothes or folding enormous piles of freshly laundered linens, or enjoy crawling on my hands and knees to pick up garbage in our Transit van—or, indeed, sweeping and mopping the floors of our home. I know my husband and kids and even I myself won’t notice much of the cleaning that a rambunctious house demands. But I can appreciate the tangible toil for what it means; that though this mess can be overwhelming, and the cleanup can seem endless, I too am part of a living ark, moving with all this clutter and chaos and vivacity toward another life on another shore. I can’t see it yet, but I know it’s coming. And someday I, too, will emerge blinking into the Light of Life that will never end in the home that was always meant for me.

Happy spring cleaning.