“Why do you seek the living among the dead?” Luke 24:5

“I’m a chap who always liked to know the worst and then put the best face I can on it.” -Puddleglum

There’s a famous story about the Christian author C.S. Lewis’s conversion to believing in God, told himself in his memoir Surprised by Joy: The Shape of My Early Life (you can read it for free here). It involves a bus ride. When Lewis got on a bus for a routine journey, he didn’t believe in God, but when he got off the bus, he did.

It’s a piquant image for us, an overly simplified recounting of a highly complex process, an intellectual and emotional battle, that had been warring within the erudite professor for his entire life. But it’s famous because it also embodies the kind of uncontrollable force that Truth—that is, the one true God—can have on us. We like to think we can grapple and weigh and meticulously consider proofs, and we can, to some extent. But when the time comes to confess, we can feel as though we are standing on a precipice, pondering a sort of wild and fearsome leap. But I think a more honest assessment, like Lewis’s, acknowledges a reality of faith: it can’t be isolated, like some control group in a sterile lab, or even usually experienced as a deliberate choice. After the Holy Spirit works on us, faith just happens.

In the last newsletter, I wrote about The Witch Trials of J.K. Rowling and, particularly, Megan Phelps-Roper, who developed the podcast. The series is asking a fundamental human question: what is truth? And how can we know what it is?

We Lutherans know. We just celebrated the Triduum, or the three days, of our Lord’s Passion on Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday. Now we are in the season of Easter, the joyous celebration of Christ’s resurrection from the dead. Easter is fifty days long, which is terrific, since the party over the defeat of death should last far longer than one day. It also fits the time that Jesus walked the earth before He sent the Holy Spirit to His followers, but I’m getting ahead of myself.

How can Christians be confident in the Truth? Not our relative truth, like that I personally love deviled eggs more than angel food cake (I am being completely honest and, yes, truthful about this). But the Truth as our reality, as our bone-deep confidence, as the unshakeable anchor when all around us falls to pieces.

One way is our grounding in witnesses and evidence. Yes, we’re back to trial language! When Jesus rose from the dead, He wasn’t seen by one or two people in one place for a brief moment. He was seen by over 500 people in multiple locations and at multiple times. The multiple Biblical accounts affirm these varied interactions people had with the Christ, the way a thorough history includes firsthand, eyewitness accounts of an event. And these witnesses revealed the same kind of evidence, over and over again: that Jesus was truly living, even though He had died. They walked with him, spoke with him, ate with him, and even touched him, particularly His scars from His crucifixion. You might hear about His disciple Thomas tomorrow in the lectionary readings, who insisted on physically inspecting the body of God.

Most of us inheritors of the primacy of logic in Western civilization would, I think, fancy ourselves shrewd brokers of the truth via the clinical standards of many witnesses and their consistent evidence. But the fact is that we don’t like to believe things that break our expectations of what’s possible. Lewis acknowledged this when he wrote about his struggle to know the Truth. His conviction of what he thought was true was indelibly shaken after a run-in with an avowed skeptic.

Early in 1926 the hardest boiled of all the atheists I ever knew sat in my room on the other side of the fire and remarked that the evidence for the historicity of the Gospels was really surprisingly good. "Rum thing," he went on. "All that stuff of Frazer's about the Dying God. Rum thing. It almost looks as if it had really happened once." To understand the shattering impact of it, you would need to know the man (who has certainly never since shown any interest in Christianity). If he, the cynic of cynics, the toughest of the toughs, were not--as I would still have put it--"safe", where could I turn? Was there then no escape?

There’s a kind of mortal foundation breaking going on here. Lewis had found some comfort in knowing that someone he respected also did not believe in God. But when that man admitted that the evidence seemed, well, true, Lewis felt lost, and indeed, trapped. He was being hemmed in by a Force greater than himself, and this was destabilizing to say the least. Lewis’s self-created understanding of the world was being shattered. Once he believed in God, he then felt himself moved closer to believing in Jesus. And that was even more unsettling.

Of one thing I am sure. As I drew near the conclusion, I felt a resistance almost as strong as my previous resistance to Theism. As strong, but shorter-lived, for I understood it better. Every step I had taken, from the Absolute to "Spirit" and from "Spirit" to "God", had been a step towards the more concrete, the more imminent, the more compulsive. At each step one had less chance "to call one's soul one's own". To accept the Incarnation was a further step in the same direction. It brings God nearer, or near in a new way. And this, I found, was something I had not wanted. But to recognise the ground for my evasion was of course to recognise both its shame and its futility.

When someone seeks the truth earnestly, he comes eventually to a particular crossroads. That crossroads is the realization that what comes next will be humiliating, because it will be a revelation of a Truth far greater and far beyond the ken of the individual himself. This Truth, by its—actually His, in the case of Christ—very nature is tangible and concrete, as Lewis put it. And real things we must acknowledge because they stand in our way, forcing us to admit their very reality. Of course, we can expend all kinds of time and energy rejecting or ignoring realities, but as Lewis realized, this is ultimately a futile endeavor. Truth will out, as Shakespeare so deftly put it, and Lewis’s tenacious evasions would crumble like Jericho’s walls before the trumpets.

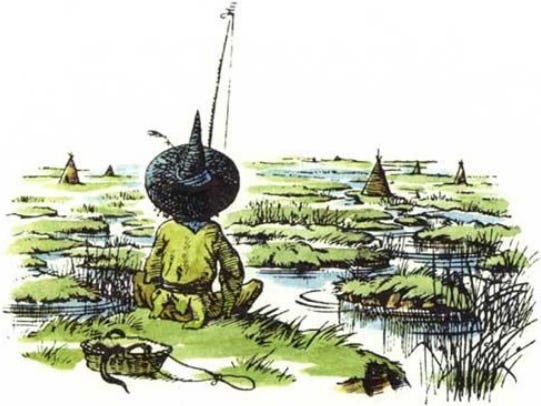

But the devil is tenacious, too, and wily. Lewis knew this, and I think this is one of the reasons he wrote The Silver Chair in his famous Chronicles of Narnia series for children. Lewis was too wise of an artist to preach; instead, he told wonderful stories that themselves testified to the Truth (not unlike the ultimate messages of Harry Potter, I would add). Silver Chair is a story of a quest to rescue a lost prince, and its protagonists are two highly flawed—that is, normal—children, the boy Eustace and the girl Jill, and their companion, a Marsh-wiggle. The Marsh-wiggle is a skinny, somewhat froglike creature, known for his endearing pessimism and unflagging loyalty. His name is Puddleglum.

The villain in Silver Chair is a perfectly realized devil’s advocate, a serpent witch disguised as a beautiful Lady. In the climax of the tale, she holds the lost prince, Eustace, Jill, and Puddleglum in the underworld where she has reigned for some time, plotting to invade the land above. She strums an enchanted harp as the scent from an enchanted fire wafts over them, and she makes them question everything they know. The witch is trying to convince them that reality is a dream, and that the dream she is spinning is reality, so that they stay enslaved to her.

The prince, the children, and Puddleglum try to resist. But the witch has burdened them with the hopeless weight of their immediate surroundings, and they stop fighting. At the last moment, Puddleglum manages to shake off the stupifying haze and stomp on the fire, which greatly weakens the enchantment. The witch loses her composure, threatening him and calling him “mud-filth” (I have to think J.K. Rowling knew this and used a similarly-sounding epithet in her books). Then Puddleglum speaks the truth about his world Narnia, and His Christ-like God Aslan, in a beautiful way.

One word, Ma’am,” he said, coming back from the fire; limping, because of the pain. “One word. All you’ve been saying is quite right, I shouldn’t wonder. … So I won’t deny any of what you said. But there’s one thing more to be said, even so. Suppose we have only dreamed, or made up, all those things—trees and grass and sun and moon and stars and Aslan himself. Suppose we have. Then all I can say is that, in that case, the made-up things seem a good deal more important than the real ones. Suppose this black pit of a kingdom of yours is the only world. Well, it strikes me as a pretty poor one. And that’s the funny thing, when you come to think of it. We’re just babies making up a game, if you’re right. But four babies playing a game can make a play-world which licks your real world hollow. That’s why I’m going to stand by the play-world. I’m on Aslan’s side even if there isn’t any Aslan to lead it. I’m going to live as like a Narnian as I can even if there isn’t any Narnia.”

There’s a persistent and compelling argument against Christianity that we all encounter. It goes something like this: “Why believe in Christ when so much suffering exists?” It’s a reworking of the underlying question, “How can Christ be true when we are surrounded by pain and suffering, confusion and darkness?” Puddleglum shows us how limited our sight is, how small our meager, mortal existences. He clings like a stubborn child to another persistent and compelling truth, which is that a world with such pain and suffering, confusion and darkness, must not be the only world that exists. It is like he stamps his foot at the witch and at her lies. I have a friend who once spoke of praying fervently to God to protect her baptized children: “You promised to take care of them! You must do it!” She is holding Him to His promises, in relentless, childish petitions, and He, who is relentless in pursuing us, always keeps His promises. This is how blind faith reaches out, in desperate, brave, and seemingly foolish confessions. It seeks the Truth because the Truth is True, and the only Truth, and we are lost without Him.

I love Puddleglum for his answer. Many would scoff at it, and more would jeer at the same answer spoken in different forms by believing Christians. But we pray that we would hold to it anyway, that no matter what kind of lies we are told, or darknesses we face, that Christ would keep us in the Truth. This is a great mystery. In this world, there is no silver bullet of logic, or witnesses, or evidence that can’t be suffused with the haze of doubt and confusion, or the terrible agony of grief and loss. But He promises to be faithful to us. In the gorgeous words of the King James Bible,

For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known (1 Corinthians 13:12).

I don’t know for sure what Megan Phelps-Roper or even J.K. Rowling believe about God or Jesus. But I do hope that they, and every person, come to know the unfailing mercies of Christ. I hope that they find the Truth, who has never been lost, but who has found us. We walk dimly in our world, but we do not walk as those who have no hope. We know where Christ says He is, and we go there, cherished what He gives us just as we look ahead. We step on the bus, and He steps us off. As Lewis wrote,

When we are lost in the woods the sight of a signpost is a great matter. He who first sees it cries, "Look!" The whole party gathers round and stares. But when we have found the road and are passing signposts every few miles, we shall not stop and stare. They will encourage us and we shall be grateful to the authority that set them up. But we shall not stop and stare, or not much; not on this road, though their pillars are of silver and their lettering of gold. "We would be at Jerusalem."

Happy Easter.