The day our son Christian was born, August 5, I labored in a quiet room.

I hadn’t want to walk into the hospital. Jon and I had gotten everything together, driven through the sunny morning to a coffee shop, then gone on to where Christian would be born. As we approached the front door, I hesitated. I almost stopped. I had known this moment was coming for months. I knew, as of earlier that morning, that Christian was dead and that he needed to be born. But I knew that once I walked through those doors, the end was near. I would walk out of them without my son. Dear Jesus, please help me.

All through that quiet day, I watched clouds form and dissipate and reform outside the window. I saw the rocking chair, meant for laboring mothers, sit empty. It was sad, but it was simple. That chair was not meant for me that day.

I was glad for the ladybug on the chair at the coffee shop, and for the sunshine and the clouds.

We’re four years out now from that blessed, terrible day. Four years from sharing news throughout that summer with family and friends that caused grief, over and again, as we experienced and re-experienced news and changes that we were still trying to digest. In truth, I still am processing what happened. But I know this: between that summer of 2019 and now, just like the Psalmist, “I would have lost heart, unless I had believed that I would see the goodness of the Lord in the land of the living” (Psalm 27:13-14).

Those of you who know us already know the following story. For those of you who don’t, or who are willing to walk with me again through what happened, this is a story of Christian.

In May 2019, we learned that we had been given a great and priceless gift—another child. In early June, I saw an ultrasound that showed some worrying signs. From that point on, Jon and I were waiting—for news, for diagnoses, for hope, for potentially the worst news that parents can hear. I remember sitting on the front porch with him after that first ultrasound, crying my eyes out, having no idea what was coming. Would our child have Down’s Syndrome? Some other congenital disease that would cause untold changes in our lives, let alone our child’s, far different from any our other children had experienced? And the worst question of all: would our child even live? I remember saying something to Jon like, “I’d rather it be Down’s or anything. I just can’t imagine losing this baby.” And he said, with all the calm steadfastness that I have seen and loved in him over the years, “Whatever God gives, we will love and care for this baby together.”

A few weeks after that appointment, we learned that our child was a boy, our fifth son. We named him Christian. The preliminary genetic screenings came back normal, but after another ultrasound with yet another visual confirmation that Christian wasn’t developing as babies normally do, we were sent to a high-risk pregnancy specialist in Denver. I will never forget what he said, and I will always be grateful for it.

“The first thing I need to tell you,” said Dr. L, “is that you didn’t do anything wrong. You didn’t use the wrong shampoo. You didn’t stand too close to the microwave. You didn’t eat the wrong thing. You didn’t cause this.

“And the second thing,” he said more quietly, “is that there’s nothing we can do.”

That’s when all of our fears from the prior month were confirmed. Christian had less than a five percent chance of survival, and he would probably not live long in my womb. Dr. L told us to go back to my regular obstetrician, Dr. M, for checks at least every two weeks. “If you were my daughter,” he said, “I’d probably fit you in once a week. Just to see if Baby is still alive.” We spoke about another high-risk appointment in a month or so, maybe even meeting with a cardiologist, but both Jon and I felt like that talk was perfunctory, a going-through-the-motions. Neither of us felt like Dr. L thought we would need that appointment.

So what did we do for the rest of that July? Jon and I decided that, as long as I felt physically able, we would to try to maintain our normal routine. This would help us cope, it would help our other children, and it would give Christian what we hoped was a little bit of normal life. The day after our meeting with Dr. L, I took the kids to a parade. It was jarring, and unreal, but it was also life. I watched the little ones run for thrown candy and mesmerizingly watch four-wheelers and tractors and floats. It was sunny and warm. We were together.

We kept on. During quiet time when some of our kids napped and others quietly played or read books, I read a book about continuing pregnancy when Baby is not expected to live. I usually cried. I cried in the shower and at night as I prayed. I would talk to Christian. “I’m sorry Mommy is crying so much. I love you.” And I talked to him about his siblings. “Boy, your big sister sure is loud sometimes, right? She loves her blanket. You hear her yelling about it a lot. She likes to snuggle with you.” She did, and she does. “‘Nuggle?” she says. “‘Nuggle?” Then she climbs over me with her blanket, what she still calls her Dida, nestles right above my belly, and comfortingly puts her finger in her mouth.

During the other times of the day, right after the news, life was quietly blessed. The kids and I sat on the patio swing or porch rockers, sometimes talking, sometimes reading, sometimes just sitting. We went swimming. We visited with friends at parks and on a few playdates. We are with generous friends who brought us food. We went on walks together. We sang songs. We watched movies together and ate ice cream and popcorn. We read books like Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel. We went to the library. We laughed together when Jon would wrestle with the kids, them screaming in glee. We prayed together and read Psalms. We went to church and received Jesus together. We snuggled a lot.

I would get emotional in front of the kids sometimes, and I could see the questions on their faces. “I’m just sad because I’m thinking about Baby Christian,” I would say. “But I’m glad we have time together.” Unfailingly, they would speak of how they loved him and prayed for him. Sometimes they would just hug me, and in hugging me, they would hug him.

At sixteen weeks, a week and a day after we met with Dr. L, I dressed up as though for church and went to see Dr. M. to see if our Christian was still alive. Jon came, too. We spoke together with Dr. M of what will likely happen, which includes induction after finding out Christian’s heart stops beating, to me suddenly going into labor with no warning. Finally, I climbed up on the table, and Dr. M got out the Doppler. I expected to hear nothing–no heartbeat. I expected to hear that our son was dead. This is what I wrote after that visit.

The relief and joy at hearing our son’s heartbeat–I can hardly describe it. Hours later, I’m still joyfully incredulous, delirious on the high of knowing he is still alive. Our son is still alive. Every moment is precious. Yes, if I think about what will probably happen, and soon, I am terrified. At the same time, I was reminded today that only God knows our times, and they are in His hands. I pray we can cherish every moment, and every day, that he is with us.

Outside of the doctor visits, life was—I don’t want to say simple, but it was simple. Eating. Drinking. Thinking. Talking. Chores. Visits. So often, simple moments were charged. The hidden thought was always there: this is probably one of the last times or the only time Christian will be here for this. Playing Horse at the neighbor’s basketball hoop with our rising fourth-grader and laughing at how bad Mom was at taking shots. Poking toes in the sandbox. Grocery shopping. Brushing the girls’ hair. Tickling the little boys before bed. Talking on the phone in the kitchen. Every day, and every week was poignant, but mostly in a cherishing kind of way. That time was special, so special. Only occasionally would I fall apart, thinking of what would never be. Seeing a plane pass overhead on a drive home and thinking, “He will never be a pilot.” Tousling my eldest boy’s unkept, sun-lightened hair and thinking, “He will never stand next to me like this.” The tears would run and run down my face the way they are running now. But I needed those moments like I needed the crazy herding kids “where-are-your-shoes-we-need-to-go-NOW” moments. They were, and are, all tied together. They are all moments of life.

At seventeen weeks, I experienced some cramping and spotting prior to my appointment. I went in, again with Jon, fully expecting to hear no heartbeat. Once again, Christian surprised me. That time, I was shocked—actually dumbfounded—that he was still alive. Once again, we had an ultrasound to see our son.

“See his feet here?” Dr. M pointed out. We marveled at his tiny toes. But I could see that something wasn’t quite right. “You can also see how they’re swollen,” she went on gently. Our son has been slowly swelling with excess fluid, most likely because his heart isn’t strong enough. It’s like congestive heart failure in adults, who deal with bloating and water retention. I had worried about pain for Christian. I hesitantly asked Dr. M about it, not sure if I even wanted to hear the answer. “Is he hurting?” What could we even do about it? But she had explained that as a baby in utero, Christian’s nervous system wasn’t fully developed yet, so he likely wasn’t feeling pain. “Also, this is his normal,” she said. “He’s never known anything different.” As I looked at his feet during that ultrasound, for the first time I thought, You need heaven.

At eighteen weeks of pregnancy, I wrote this.

Yesterday. Another week, another appointment. We were silly, waiting with the big boys who’d just had dentist appointments, telling them a story about me that made them embarrassed, grinning, and acting like they didn’t want to hear any more. They stayed in the waiting room when Jon and I went back.

Instead of the Doppler first, due to a nurse shortage, we had an ultrasound. We saw Christian right away, a white figure moving in the black on the screen. His heart thumped. Da-dum. A pause. Da-dum. Another pause, a little longer. Da-dum.

Both Jon and I thought, “Maybe Dr. M isn’t holding the wand right.” We all watched Christian move for a moment, the lines from the erratic beating creating a messy pattern below him, the sound of his heartbeat a pausing, uncertain staccato-like sound. Then Dr. M said quietly, “So you can see how his heartbeat is irregular.” My eyes blurred, and tears ran down my cheeks.

This was stark and real. Christian’s slowing heart was telling us the end of his time on earth was fast approaching its end, and though we’d expected this, I suddenly ached, almost gasping. No! Not yet! my heart screamed.

I pulled it together. In spurts, I managed to ask, “Is there any way to know how long he could make it?” Dr. M was already shaking her head. “His heartbeat could have been irregular before, and we just missed it. Or it could have just started its irregularity. He could last a week or just a day–we don’t know.”

It was surreal time, those last days of July into August. I write about them now, and again, not just because I want to remember them, which I do. It’s also healing for me, even as it is hard to think about. I want to know that our time with Christian was real, and I want cherish what we were given even as we were grieving. I wrote just before he died, “This has all been so surreal and yet real at the same time. I don’t really want to sleep—I want to be awake as long as he is with us. As I write this, I think I just felt him kick. That started last week—the fluttering kicks of his quickening. I never thought I’d experience that. It is an extra gift, just as he is.”

After the appointment when we first heard his faltering heartbeat, I choked back sobs and talked to Christian as I lay down to sleep.

“You’re going home soon, Baby. Home to Jesus. He loves you more than all of us combined.” He died so Christian will live. His body will be perfected and on the last day, he will rise with a terrifically strong heart. The kids gave me hugs last night as we told them Christian’s time was short with us. “Tell him you’ll see him again,” I said. “We love you, Baby!” our five-year-old yelled. “See you in heaven!”

Grief is a funny, sneaky thing.

The pain of loss is mostly dull, like a quiet ache that one learns to accept because it doesn’t disappear. I expect it at certain times. At church, always at church. Driving past the cemetery. Reading and re-reading a condolence card. These times make sense. They have been and still are direct reminders of Christian and why we mourn.

Sometimes I can feel grief coming, like a creeping storm, like the approach of August 5. Shortly after Christian died, Jon stopped by our kids’ school, where another volunteer and I were cleaning and organizing in the library. School was still starting soon, and I was still the volunteer librarian. Jon and I went by the stairwell to talk. He’d ordered the headstone, but after seeing more options, he wanted to see if I wanted something different. I felt a wave of helpless indignance: why is even death in our culture drowned by consumer choices? But Jon was being thoughtful to me. We spoke briefly, but I could feel grief rising, the emotional crest threatening to crash. I just couldn’t switch from school mode to grief mode. “I’m sorry. I can’t talk about this anymore,” I said, abruptly. He nodded. He got it.

Sometimes grief flares up sharply, cutting my breath and choking my throat, at times I least expect it. On a hike with my daughter, after just marveling at the wonders of the view on the mountain, I saw silvery-green leaves quivering in a soft breeze. Why should the shimmer of leaves, when a moment before I was alive and joyful to the wonders around us, make me want to weep?

How do people live with this? I think. I know of hard cases, the ones that I think, in different ways, would be more difficult to bear. The years-long cancer patients, slogging through treatments and dealing with their bodies slowly decaying. The widows and widowers who’ve lived alone for years, sometimes decades. The women who have experienced traumatic stillbirths. The parents who’ve buried three adult children, all of the children God gave them. And yet how can anyone learn to live with this or any suffering except to slog through it, to labor and be carried?

“Come to me, all you who labor and are heavy laden,” Jesus said, “and I will give you rest” (Matthew 11:28). I heard a pastor preach this summer about a yoke, and how it can be adjusted so that one animal takes the brunt, or even all, of the burden. Christ does this for us. He asks us to rest and to trust Him. At the same time, it’s notable, I think, that the burdens—the crosses—are still there, even as He bears them. We still know they exist and are real.

Grief can be exhausting. I wrote this a few weeks after Christian died, after I’d written down some theological thoughts pertaining to grief. “I stand here, fully caffeinated in the morning, dishes washed, list getting checked off. I’m in my prime time. And after thinking about and writing these few words, all I want to do is crawl back into bed and sleep, deeply and without dreams.”

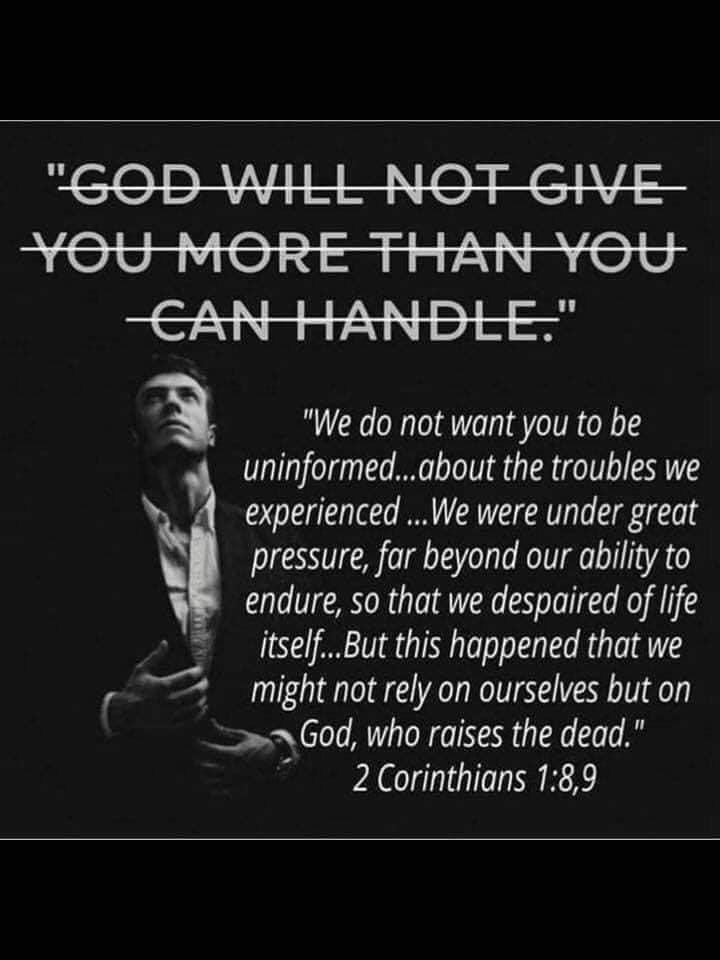

Yet I went on. Some of it was out of necessity. What else could I do? People were so incredibly kind, sympathetic and encouraging. “You are so strong.” “Thank you for your witness of Christ.” I was grateful for their words, but my thoughts were and still are garbled, struggling to reconcile the incongruity. I know hope during grief is good, but I did not and do not feel good, or at least worthy of any special attention. This is gagging on a translucent, existential gnat to most people—the vast majority just mean to be sincerely supportive, while a small part of my brain heard them presupposing some herculean act of will on my part, Emily the Mighty Sufferer, standing athwart hopelessness and yelling, “Stop!” But I knew then and know now that I am utterly powerless, and I still can’t help feeling uncomfortable with comments like that, even when they aren’t directed at me. What else can I do? What else can anyone do?

Beside the daily need to keep moving, keep doing the work in front of me, I have learned to wrestle with harder truths. As I wrote in 2019,

My choices seem woefully stark. Truly, all I can do is either reject God or surrender to His mercy. To definitively reject Him is to enter a darkness that frankly scares me more than it entices me, though the temptation to push away is real and angrily persistent. But I am so afraid of the hole that rejection presents that this means that it’s not an option. So I surrender to God’s mercy, to Christ’s bleeding hands. And even the surrender is weak and childlike, like a newborn mewing sibilant cries for food. He does not even reach for the nutrients he so desperately needs. He opens his mouth in helplessness and need. That’s all. Just as I lay, one day old, before a pastor in a hospital room, baptized into Christ in tiny weakness, I turn again into that premature babe. I am not yet grown. I do not yet understand.

Rev. Dr. Gregory P. Schulz knows this cognitive searching. In The Problem of Suffering: A Father’s Hope, the pastor and philosopher, husband and father watched and wrestled as two of his children suffered and died. Kayleigh, his daughter, was almost one year old. Stephan, his son, was fourteen. “I often look at the crook of my right elbow and know it as a sacred place [the last place he held his son, Stephan]. Now I want to understand, if I can, what it means for me to feel the way I do, not just about Stephan’s suffering and death, but how I feel toward his God.”

I know how he feels now. I too confess the hope of the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come. Cognitively, I believe this. Theologically, I cling to this. Emotionally, I break under this necessity—that we die, that we are dust.

I visit Christian’s grave alone sometimes. They are quick stops to clear away fresh flowers that have withered—how incredibly fast they wither and brown—or to place new, artificial flowers, and to pray. I gaze at the mountain and take deep breaths in the quiet of the trees and wind-swept stones. I watch the antelope that quietly graze in the clear spaces between the dead.

There’s another reason I go, which I wrote about in the months after he died.

I visit my son’s grave to place my hand over him. I can still see the place where men cut away the grass to turn it back before the hole, the hole that holds the small box in the earth where our son’s body lies. I grip the grass, and smooth it, and I can’t seem to stop wanting to touch it. Because, I realized, it’s the closest I have to touching my son in this life. I weep when I touch the grass, and I weep writing this. Weeping is part of my soul’s rejection that death was ever supposed to be a part of life.

The visceral experience of carrying Christian while he both lived and died crushed me. The only way I can survive with my arms empty of his life is that my, and his, only salvation is in the hope of the resurrection, of Christ reconstituting his ashes, and likely eventually mine too, back into life.

This remembrance eases my tears, and I go on. I rest in Christ, the only One who keeps me going. And it is getting easier, not because the grief goes away. But it ebbs and flows, and Christ is constant. He is always constant. His mercies never end.

I am truly thankful for this day. On this day, I had an experience that is priceless—to hold my son and cherish him, even as he was already asleep in Christ. And on that day and those surrounding it and ever since, Jesus continues to show me His grace. The burden I absolutely could not carry myself continues to be carried by Him who yoked Himself to me and to my son and to all believing Christians. That I have lived, and continue to live, this is a gift and an eternal mercy.

We will see and hold you again someday, Christian.

God’s blessings, mercy and peace be with you, Jon and the children, Em. I love you.